Guest post by John Wilson, Lost Rivers Project

A few weeks ago my friend Joanne Doucette sent me an amusing email with the Subject line “Holly Brook”. It included a Toronto Star clipping from April 11, 1907, reporting on a request that the city build a box drain on the property of the Phillips Manufacturing Company on Carlaw Avenue. The drain would divert a natural watercourse flowing near where the company wanted to lay the foundation of its new factory building. Also attached to the email was a composite photo of Joanne’s own face with a dead crow apparently poised on her lips.

Now Joanne Doucette has no need to eat crow. She is very arguably the foremost Leslieville historian. She literally wrote the book – Pigs, Flowers and Bricks: A History of Leslieville to 1920. But Joanne and I have had a disagreement brewing for several years as to the exact location of Holly Brook a.k.a. Heward Creek, one of a dozen or more “lost rivers” draining the eastern Toronto waterfront between Scarborough Bluffs and the Don River.

Determining the former course(s) of streams and creeks that city engineers have buried, diverted or otherwise trashed to prepare the ground for building our rational, grid-patterned city is the self-appointed job of a small collection of Lost River walkers associated with the non-profit, charitable Toronto Green Community. The job entails iterative research, ground-truthing, collaborating, outreach and documentation. Lost River is a project founded by Helen Mills, recognizable largely due to the lostrivers.ca web site created by the late Peter Hare. Today the web site needs wholescale updating, but the project moves forward in large part through the diligence of the Lost River Walks program to which I contribute. We are a small community of activists and academics, urbanists and naturalists, all of us geographical historians in some way.

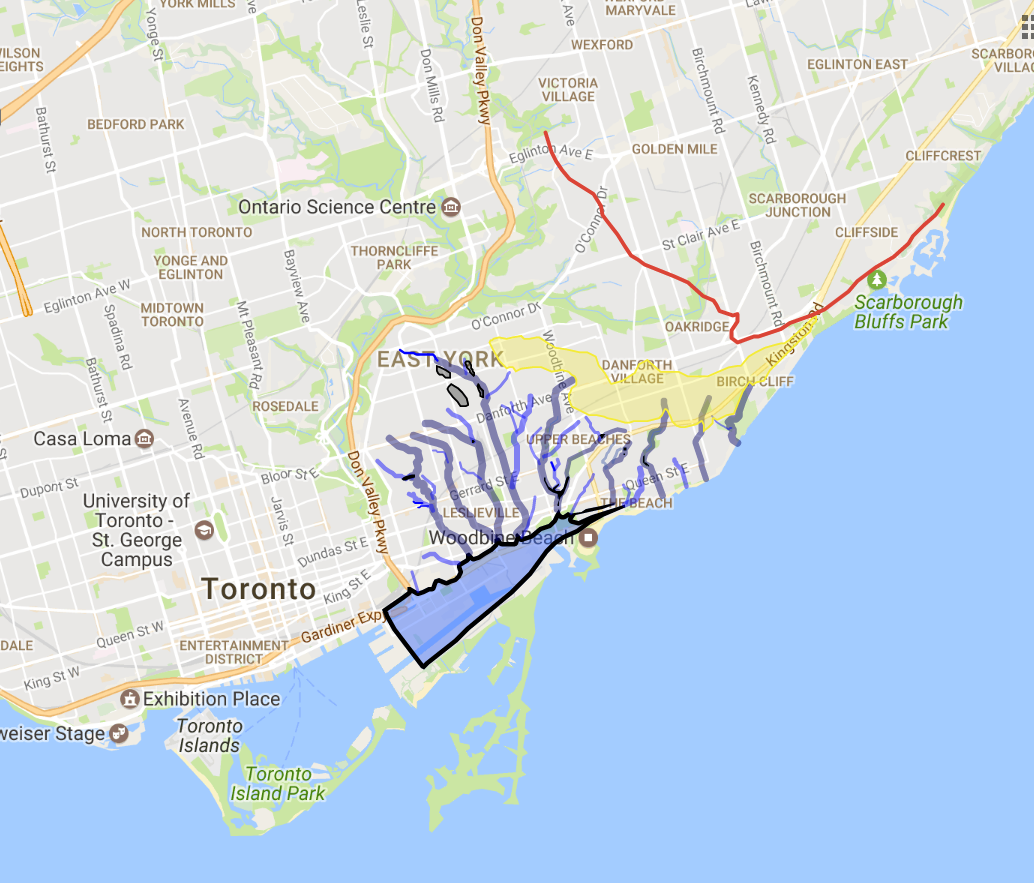

On Holly Brook there is contradictory mapping. The creek is the closest East End stream to the Don River and central Toronto.

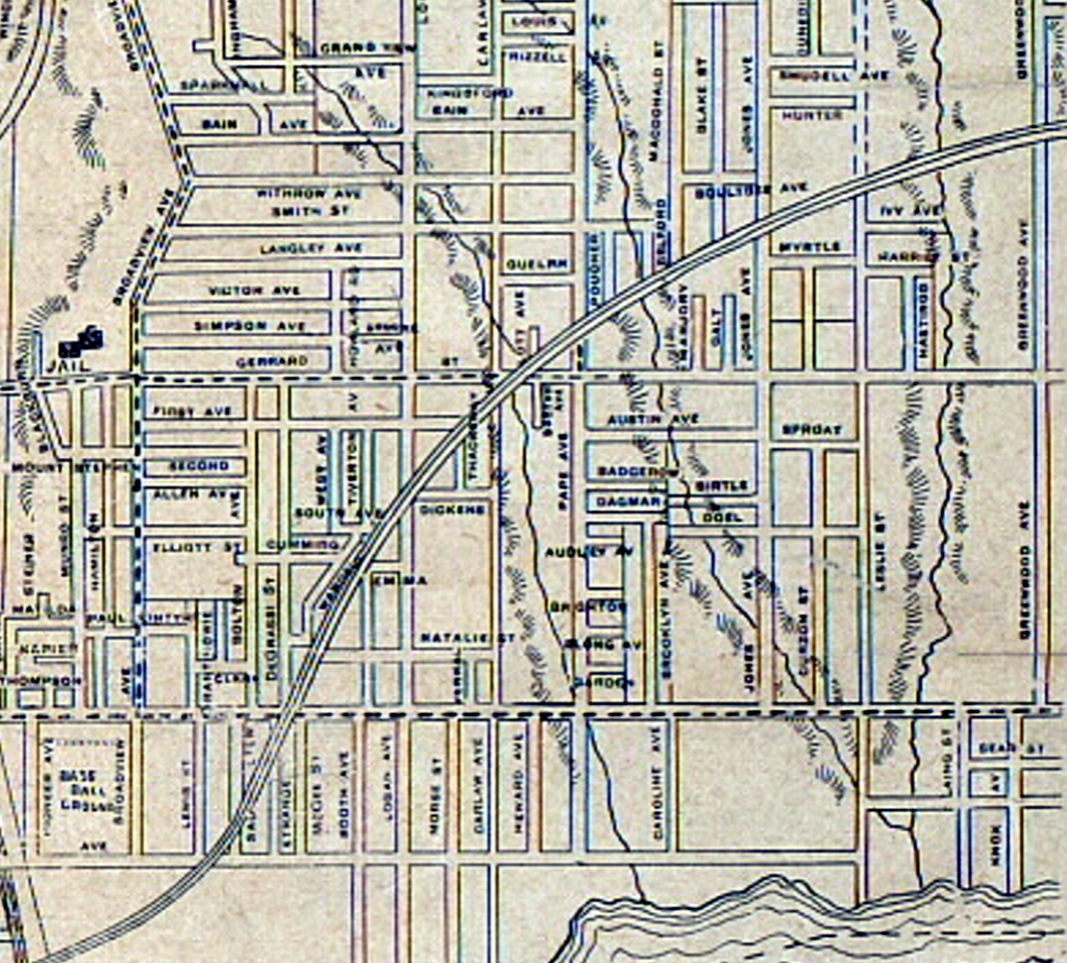

With urbanization it was filled completely and early – by the late 1800s. The creek’s lower courses were severely altered by John Russell’s brickmaking operations. Maps issued by the City Engineer’s office in the 1890s showed a watercourse flowing south between Gerrard and Queen Street well east of Carlaw, as shown in this map.

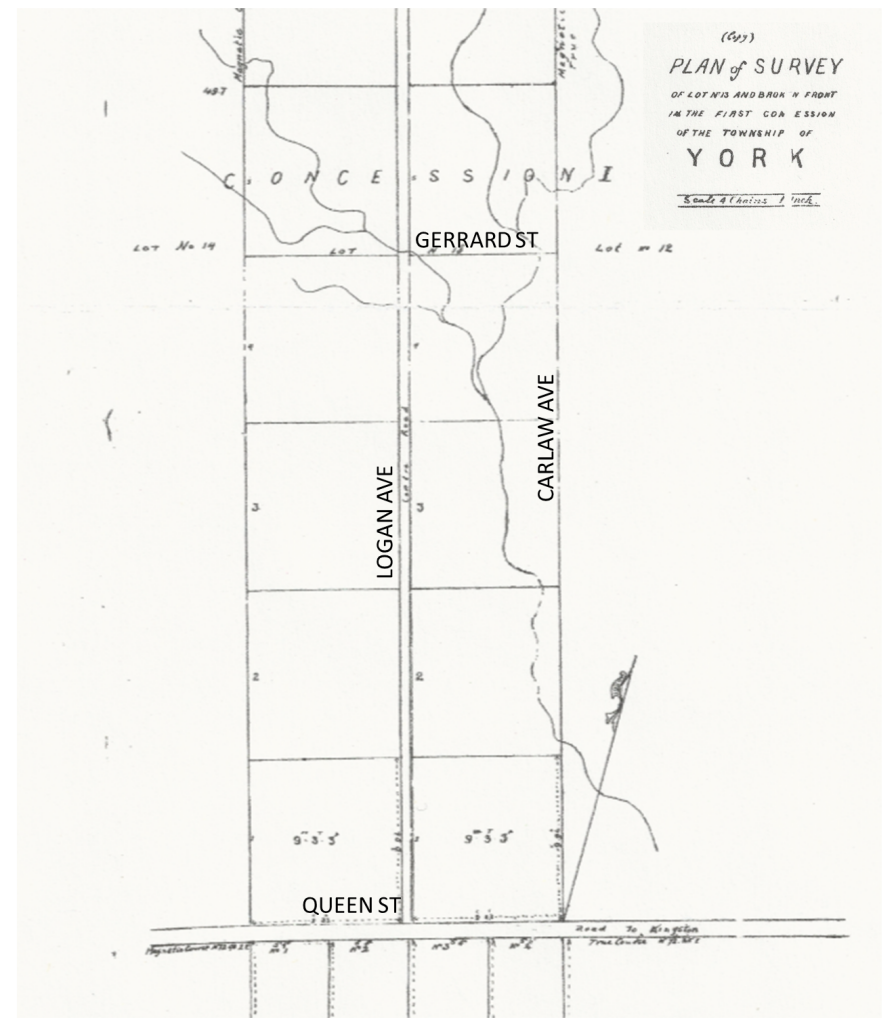

But one map, a Plan of Survey of Lot 13 dated 1884 (but showing internal indications of having been based on a much earlier survey), details the watercourse flowing west of Carlaw until it crosses at the location of the Phillips building discussed in the 1907 Star clipping.

I have spent many hours travelling the city’s streets and laneways looking for signs of lost rivers and ravines. My street-level observation of Holly Brook’s course was simple – whatever the City Engineers may have drawn on 1890s maps, water doesn’t flow uphill! To understand the watershed of historic Holly Brook another hypothesis is necessary, one that corresponds to the data on the Plan of Survey of Lot 13.

For lost river aficionados this kind of exploration is more a passion than a pastime. Our memory bank, gathered from explorations and shared with colleagues on Lost River Walks, represent data sets as yet under-documented in the layering of geographical information that is coming together in, for example, the Don Valley Historical Mapping Project, to which we remain a committed partner.

Holly Brook’s historic course may seem solely scholastic, but my experience is that this kind of enquiry teaches us valuable lessons about the building of our city and about living sustainably within our community. It helps us express important values about our place and the place of nature in the 21st century urban environment.

Today young people in households of one, two and sometimes more are recolonizing the former factory buildings on Carlaw Ave. Across the street from the former Phillips Manufacturing Company site, where Holly Brook undermined the foundations, the Rolph-Clark-Stone lithography building is now home to a new Leslieville condominium community. How many are puzzled by the deep basement windows facing Carlaw that peer out below sidewalk level? These windows seem to reflect the condition at the time of construction when the building’s foundation was laid far below current street level, buried deep into the former Holly Creek bed.

This sort of observation demonstrates how Lost Rivers provide clues as to why the city has been built in just the way it has been. Other common examples come from the street grid. Toronto’s main rectilinear layout is disturbed when streets are broken (example, St. Clair) or mysteriously jog (example, College), to accommodate a creek crossing. Similarly, diagonal off-grid streets often follow a height of land between streams (examples, Vaughan, Danforth Road). The engineering of rail lines had to take into account the landforms created by watercourses. These decisions have impacts upon subsequent city-building that echo over centuries.

Holly Brook’s effects recently “surfaced” again. Toronto’s Transportation Division and the TTC are planning a subway “Relief Line” (sometimes called “Downtown Relief”). The line will run south from Pape station at Danforth Ave., but stakeholders in Leslieville are struggling over a choice between a Pape or Carlaw orientation for the subway tunnel. Pape is a quiet residential street near Queen, while Carlaw is a bustling, mixed-use artery. It seems that Carlaw would be a better choice for the tunnel, but for one issue. Below Carlaw there flows a combined (stormwater and sanitary) sewer – the remnant of buried Holly Brook flowing south from Playter Estates, past Withrow Park, through Riverdale. Further, an east-west combined sewer along Gerrard St. diverts the some of the flows to Ashbridge’s Bay Treatment plant. A subway line below Pape could be tunneled below these sewer lines, but along Carlaw these sewers would have to be rebuilt. The cost premium for building below Carlaw, where buried Holly Brook flows in its degraded, post-industrial form? Around $300 million!

This is a point where Lost Rivers research seems more than solely academic and becomes more directly activist. Toronto will not “replumb” all its streets any time soon, but there are ongoing, recurring costs in treating water as a barrier to growth, rather than as a resource. If the flows of streams like Holly Brook would be naturally integrated into the urban fabric, they could become a natural and social benefit, rather than just barrier to city-building.

With examples like this the Lost Rivers project seeks to overlay historical mapping, storytelling, archival image collection, water infrastructure documentation, and personal responsibility to contribute to an enhanced collective dialogue about care for Nature in the City – air, water, land, other species and one another – in a way that sustains life through this century and beyond.