— the benefits of the long-tail of the Ontario Historical County Map Project and the Don Valley Historical Mapping Project data

Most academics who’ve written about Historical GIS have discussed the high-cost of building HGIS projects (Gregory and Ell, 2007). Building any GIS project is an expensive endeavour. Few, however, have mentioned the benefits of the ongoing nature or the extended length of some projects; and the long-term benefits of data projects Ontario Historical County Map Project (OCMP) and the Don Valley Historical Mapping Project (DVHMP) are two projects that have benefitted from the long-tail of their existence in order to continue to develop and enjoy useful applications and use of the long-ago-built (or still being built) historical data.

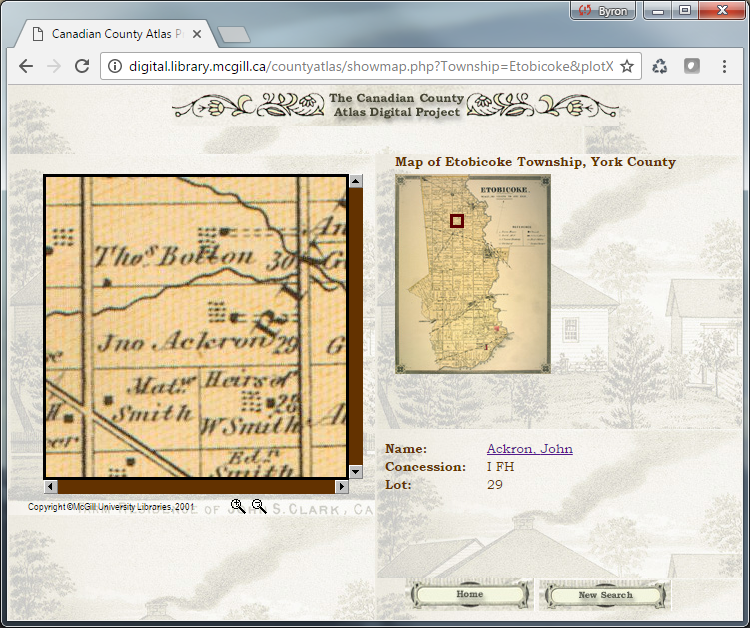

The OCMP was conceived a few years after the release of the well-known Canadian County Atlas Project at McGill University Libraries in the late 1990s. Nineteenth century County Maps were generally published earlier than the County Atlases. The Atlas project focused solely on the bound maps, and the OCMP focuses only on the earlier large-format maps. Like the Atlas project, however, the main focus of the County Map Project is to allow for the querying of land occupant names found on the maps, and the display of the names on images of the historical maps.

While the McGill project did not use any GIS technology for displaying name information, it did take advantage of the web-technology of its day to graphically lay-out images of the atlasplates, and PHP to link image locations within the database of land-occupant names. The Atlas project was certainly an inspiration to us in developing the Ontario County Map Project.

In contrast to the types of tools used in the Atlas Project, the OHCMP has been a GIS project from the beginning. Like the Atlas Project, however, we also wanted to ensure that users of the County Map project could benefit from web technology to view the maps and GIS data. Being a GIS database, however, a new method of dissemination would need to be used.

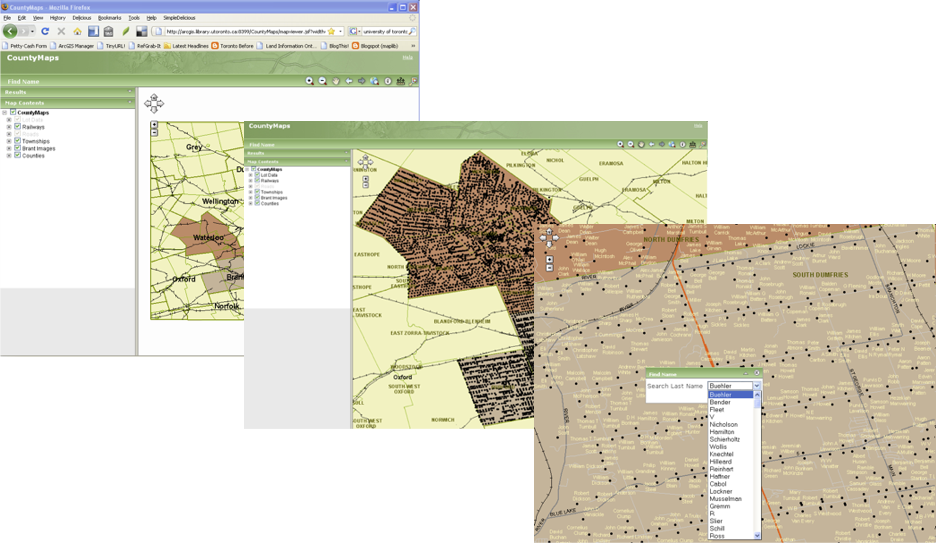

Early tests of web technology were pre-Google and used what is now archaic web-mapping software. Our first attempt in 2004 utilized Esri’s ArcIMS (Internet Map Server), made available to us as part of our campus site license with Esri Canada. We loaded our entire database into ArcIMS as a test, which at the time consisted of only Waterloo and Brant counties. Somewhat surprisingly, we were able to build a sophisticated querying tool and managed to display the georeferenced county map scans in the online map.

While yielding relatively impressive results for the time (if one were patient enough to wait for results of a query or a zoom-in or -out) it was clear that this setup was less than ideal as the software was extremely difficult to install, very slow to render results, and gave us difficulties finding adequate server space on which to permanently install the software.

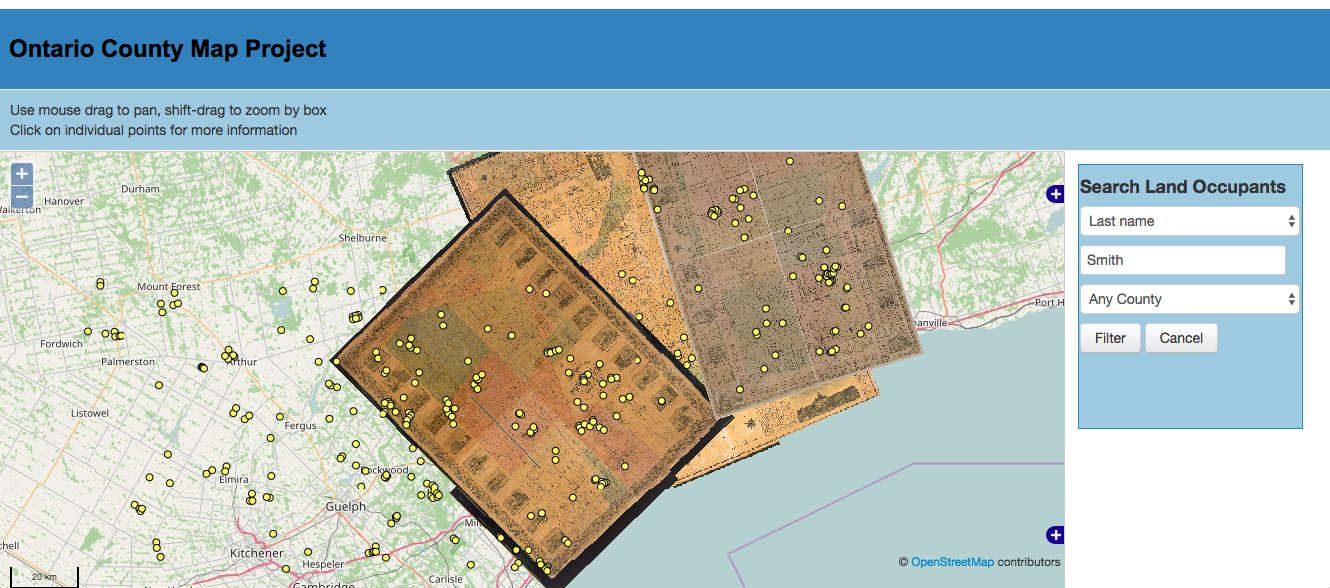

Due to the limitations of available software, developing a web map of the land occupant names of the project was put on hold. Of course Google Maps changed the entire web-mapping landscape in 2005. Despite the adoption of Google Maps by many to display their data on the web, our attempts were hampered by the now large size of our land occupant database. While MySQL was often used to work alongside PHP and the Google API at the time, the conversion of our geospatial database into a MySQL database would have been a step back in the GIS development of the project.

Other more recent attempts at using web-mapping technology in 2013 also included a Mapserver configuration with OpenLayers and a PostgreSQL geospatial-enabled database using PostGIS. While the shapefile data did need to be converted to PostGIS, this setup at least promised the maintenance of our database in a GIS environment, compared to using MySQL. The resulting web-map was very promising, but required quite a bit of coding and manipulation. Having no programmer on the team or any funds to hire one, my programming of the application was limited to a six month research leave and the odd-slow day at the Map and Data Library. Without a programmer, it was clear this solution was less than ideal and would take years to complete.

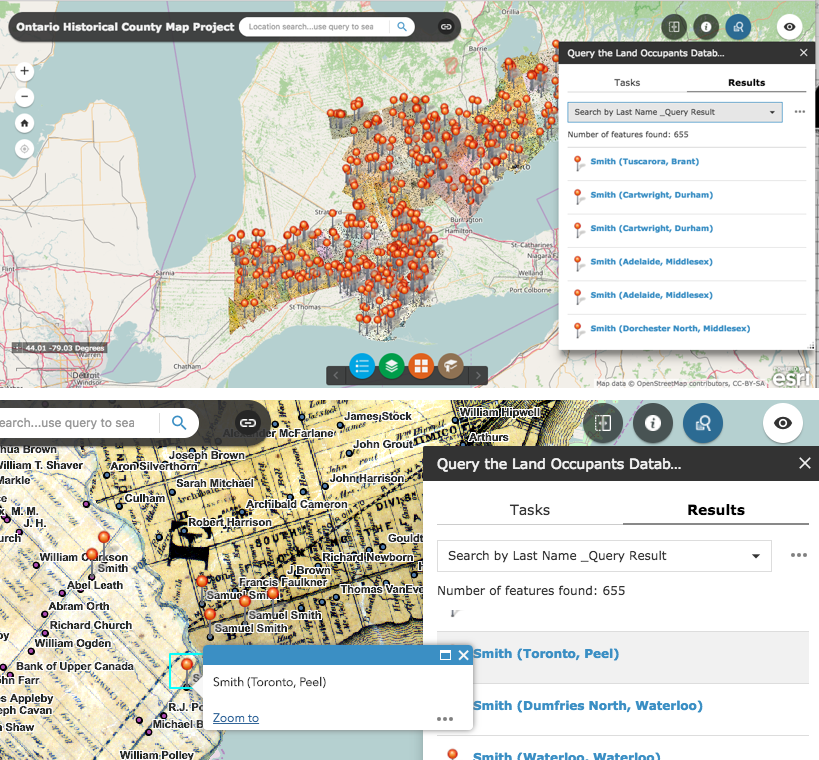

For many years I ignored ArcGIS Online as possibly an overblown idea by Esri. How could one actually build an online tool with GIS functionality and get us to buy into it, I always wondered. However, its popularity grew so much among our U of T users that I eventually needed to learn how to use it to be able to support it. What better way to teach myself how to use ArcGIS Online than to load the County Map Project data, I decided. To my immediate surprise, ArcGIS Online was not only fun and full of great GIS and web-mapping features; it also had the Web AppBuilder application built into it. Along with dozens of Story Map templates, the Web AppBuilder allows you to take your GIS data into a web skin where you can add customizable widgets that work extremely well, even in mobile browsers. Being able to query or filter the 80,000 or so names in our database was a key consideration in adopting any web technology for the project. ArcGIS Online delivered this amazingly well, and also allowed for the rendering of high-resolution images of the scanned County Maps. The ease of use and customization of web apps without the need for coding are also fantastic selling points. Other fun but useful widgets include using animated timelines of “time-enabled” data, and a swipe tool that allows for viewing two datasets on top of the other and sliding a toolbar to switch between displays.

Adopting ArcGIS Online as a web-mapping tool has allowed the project to be out in the public eye where users can actually take advantage of the data built over the past 15 years. I never thought we would have a web-mapping solution before we finished the database, but as it stands, I am pretty happy with most of the functionality of the web app at this point, as our database continues to grow and we continue to compile more land-occupant names from Historical County Maps. Interestingly, while writing this post I actually received three email messages about the project and requests for further information from users of the County Maps site. Without making our data available in this powerful way, I doubt our project would have drawn so much attention.

Inspired by my success with the web-app builder tool, I decided to also build an app for the DVHMP and found that the data we had built over seven years ago really came to life on the web. Being able to query the data and render both polygon and point data together in one view online is empowering.

ArcGIS online is of course not the only tool that has taken advantage of web-mapping and cloud computing advancements to allow users to build their own web map apps. Products such as Mapbox are also increasing in popularity because of their ease of use, powerful functionality and customizability, and the attractiveness of the final map product.

Web Mapping has been around since the 1990s, but with new advanced web-mapping technology like ArcGIS online and Mapbox, it may be time for many other dormant or long-forgotten HGIS datasets to be pulled out of hard drives, or USB sticks to be given new life displayed in easily created yet powerful web maps. I am excited at the thought of possibly seeing the Montréal Avenir du Passé data for instance, available for display on a web map for all to interact with.

The Canadian HGIS Partnership is investigating many web-mapping tools and visualization methods. We are also working with Esri Canada, as part of the GeoHist project, to provide specific HGIS requirements for online mapping tools. With the powerful components already available in ArcGIS online, Mapbox, and other web mapping tools, the future of web-mapping for HGIS is certainly very exciting and accessible to anyone interested in developing them without the need to code.

References:

Gregory, Ian., and Paul S. Ell. Historical GIS: Technologies, Methodologies, and Scholarship. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.